Decoding Pregnancy Loss with Leela Biswas

2022 AMA Research Challenge Winner

When I was struggling to conceive my daughter, I had a complicated relationship with statistics.

I searched frequently on Google in the first few months, reassuring myself that the vast majority of healthy couples (85%, according to the American Pregnancy Association) achieve pregnancy within a year. As each month passed and it became increasingly clear that I would fall into that unenviable 15%, I became less and less eager to calculate my specific odds of family-building success.

Statistics – some hopeful, others discouraging – appear constantly throughout the fertility journey. Odds of conceiving naturally. Odds of conceiving through IUI. Odds of conceiving through IVF. Odds of experiencing miscarriage.

This latter figure comes with statistics of its own. Most miscarriages are the product of a genetic abnormality: a chromosomal mutation that makes the embryo incompatible with life. While this may be encouraging to most healthy young women, who largely have a robust collection of genetically normal eggs, it can be devastating to those who don’t.

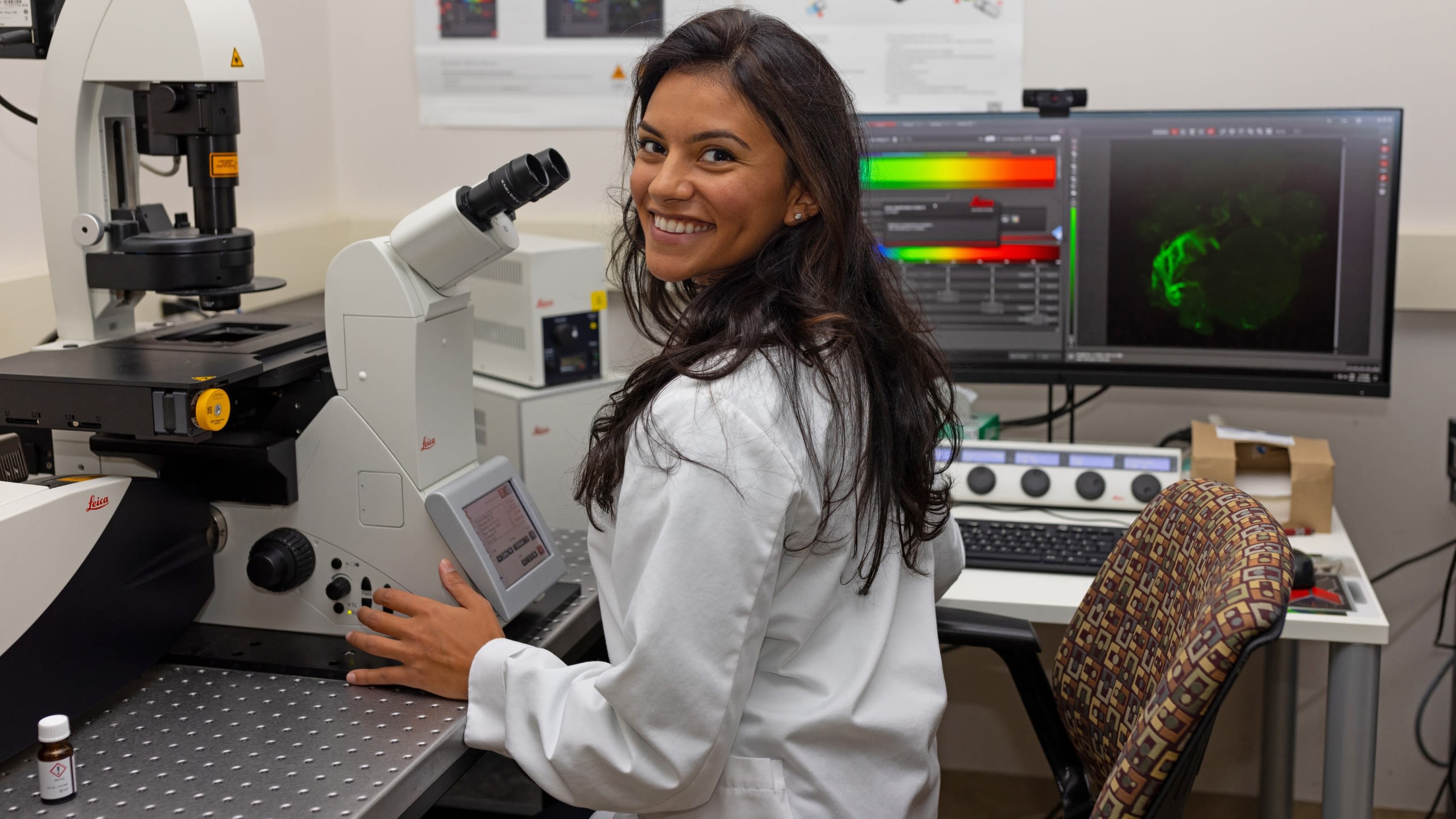

Leelabati “Leela” Biswas, an MD/PhD student at Rutgers University, had these people in mind when she set out to identify a genetic biomarker associated with poor egg quality and associated miscarriages.

Her research yielded results: under the guidance of Dr. Karen Schindler, an associate professor at the Human Genetics Institute of New Jersey and the Department of Genetics at Rutgers, Leela identified a genetic mutation that was sufficient to increase the rate of genetic abnormality in eggs.

For her work, Leela beat out nearly 1,200 submissions to win the 2022 American Medical Association (AMA) Research Challenge, the nation’s largest multi-specialty student research competition.

Genetics: A Core Driver of Egg Quality

Picture this: you’re 28 years old, and you’ve decided it’s the right time to try to build your family. You spend a year or more trying and failing to conceive, your path peppered with recurrent emotionally and physically grueling miscarriages. You wind up in the IVF clinic, where you learn that you have a high rate of aneuploidy (that is, chromosomally abnormal eggs) -- a highly atypical finding for your age.

“That’s really devastating,” says Leela. “The IVF paradigm is retrieving oocytes and making embryos. It’s really devastating when that doesn’t work.”

It can be especially devastating and unexpected for younger women with no known risks for infertility and who, according to their age, should still be well within the window of optimal egg quality. “While that curve [of the relationship between maternal age and egg abnormalities] does represent on average the whole population, there are outliers,” says Leela. “There are some people who are young who have a whole lot of abnormal eggs. And there are some people who have advanced maternal age who have totally chromosomally normal eggs, which is not what you’d expect.”

Leela was interested in delving deeper into this pool of outliers. “There has to be something other than the typical age-related mechanisms at play for those individuals,” she said. “We decided to investigate how genetic variations influence egg quality to determine what’s driving this age-disproportionate change in quality.”

Leela conducted her research in the lab of Dr. Schindler, who has been interested in this very question for nearly a decade. “Probably a year after I started [at Rutgers], [my colleague]…showed me the data on how with increasing maternal age, you get a signature curve of aneuploidy, but there were patients who were all over the place,” says Dr. Schindler. Over the next several years, she and her colleagues began investigating whether a genetic link could explain age-unrelated aneuploidy.

“When Leela came online, we knew that we had this family of proteins called kinesins,” explains Dr. Schindler. “Leela was helpful in screening them, and she was captured by the interesting phenotypes of this particular kinesin called KIF18A. That’s how her project started.”

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

The Project

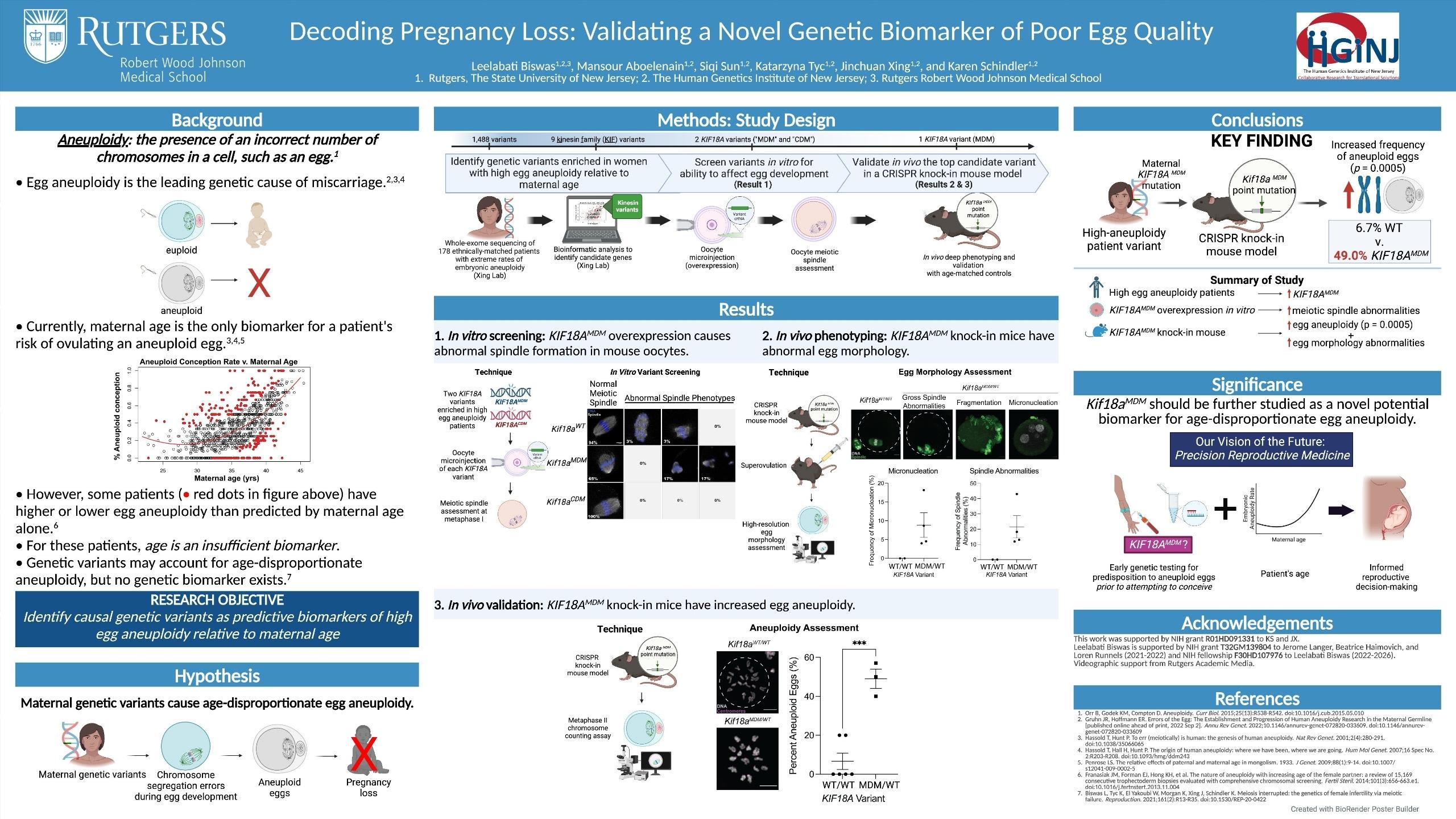

Leela worked within Dr. Schindler’s lab to review bio samples from nearly 3,000 patients who demonstrated high rates of aneuploidy relative to their age, then identified genetic variants within this population using genetic sequencing.

She created a mouse model to study whether certain genetic variants, including KIF18A, could be causally associated with poor egg quality.

“With a mouse model, we move into a biological system and test [the variant] in cells,” she explains. “We ask: if we keep all the other genes exactly the same and just change this variant, can we make eggs that are chromosomally abnormal?”

Leela conducted this experiment with a number of variants and screened several mutations she had identified in high-aneuploidy people.

Ultimately, she found that KIF18A was sufficient to increase the rate of genetic abnormality in the mouse eggs -- which suggests similar rates of aneuploidy in human eggs.

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

What A Genetic Biomarker For Miscarriages Means For Those TTC

To Leela, identifying KIF18A’s association with aneuploidy is a first step in better understanding an individual’s risk of miscarriage.

“[The mouse model we constructed] helps to establish this variant as causal,” Leela explains. “That needs to be done with many different variants, so we could ultimately develop a panel to understand an individual’s fertility profile.”

The hope, according to Leela, would be to help individuals understand their genetic assessment well before they begin trying to conceive.

While Leela studied the particular phenotype of increased aneuploidy relative to age, she notes that multiple genetic variants exist that are known to affect egg quality. She references one case of a genetic encoding beta tubulin that causes oocyte maturation arrest: a condition in which oocytes do not mature and cannot be fertilized.

“There are something like 50 different variants listed in the databases that are associated with pathogenicity in that particular phenotype,” she says. “And yet, that’s not a genetic test that’s routinely ordered. Some of that is clinical reasoning -- most people don’t have any of those genetic variants. But if you are that person who does, it would be nice to know. It’s nice to be empowered and to be aware of what’s going on inside your body.”

In Leela’s ideal future state, women could be empowered with this information by way of a simple blood test, which they could undergo months or even years before they begin trying to conceive.

“In this era of genomic medicine and the DNA sequencing revolution, we deserve to have insight into how our bodies work and what’s going on,” says Leela. “The technology is there. That, I think, is a point of urgency for women everywhere. It’s career-changing. It’s life-changing.”

To Dr. Schindler, who has devoted her career to studying these questions, it’s foundational. “If I were [a fertility] patient, I would want to know why we understand so little about something that is absolutely essential to our lives on this planet,” Dr. Schindler says. “I think about the billions of dollars that go into cancer research. We wouldn’t have cancer if we didn’t exist. Reproductive science is really fundamental to everything else, and yet it is extremely underfunded.”

As she moves to the clinical phase of her MD/PhD program, Leela is undecided about what specialty she will pursue, but one thing is certain: she is bullish on precision medicine, particularly as it relates to reproductive endocrinology and infertility (REI).

“One of the amazing things about fertility and REI as a field is that everyone is always seeking to improve,” she says. “People are doing amazing things, and bringing precision medicine and better genetic testing to empower people before they’re starting to try to conceive is the future.”

See Leela find out that she'd won the 2022 AMA Research Challenge!

Molly Donovan is a writer and content strategist who helps brands and executives develop actionable communications and content strategies and create compelling, authoritative content.

While she loves words, the best thing in her life is her daughter, for whom she and her husband are endlessly grateful to the incredible team at the Brigham and Women’s Center for Infertility and Reproductive Surgery.

You can learn more about her at mdonovancontent.com.

When I was struggling to conceive my daughter, I had a complicated relationship with statistics.

I searched frequently on Google in the first few months, reassuring myself that the vast majority of healthy couples (85%, according to the American Pregnancy Association) achieve pregnancy within a year. As each month passed and it became increasingly clear that I would fall into that unenviable 15%, I became less and less eager to calculate my specific odds of family-building success.

Statistics – some hopeful, others discouraging – appear constantly throughout the fertility journey. Odds of conceiving naturally. Odds of conceiving through IUI. Odds of conceiving through IVF. Odds of experiencing miscarriage.

This latter figure comes with statistics of its own. Most miscarriages are the product of a genetic abnormality: a chromosomal mutation that makes the embryo incompatible with life. While this may be encouraging to most healthy young women, who largely have a robust collection of genetically normal eggs, it can be devastating to those who don’t.

Leelabati “Leela” Biswas, an MD/PhD student at Rutgers University, had these people in mind when she set out to identify a genetic biomarker associated with poor egg quality and associated miscarriages.

Her research yielded results: under the guidance of Dr. Karen Schindler, an associate professor at the Human Genetics Institute of New Jersey and the Department of Genetics at Rutgers, Leela identified a genetic mutation that was sufficient to increase the rate of genetic abnormality in eggs.

Dr. Karen Schindler and Leela Biswas

Dr. Karen Schindler and Leela Biswas

For her work, Leela beat out nearly 1,200 submissions to win the 2022 American Medical Association (AMA) Research Challenge, the nation’s largest multi-specialty student research competition.

Genetics: A Core Driver of Egg Quality

Picture this: you’re 28 years old, and you’ve decided it’s the right time to try to build your family. You spend a year or more trying and failing to conceive, your path peppered with recurrent emotionally and physically grueling miscarriages. You wind up in the IVF clinic, where you learn that you have a high rate of aneuploidy (that is, chromosomally abnormal eggs) -- a highly atypical finding for your age.

“That’s really devastating,” says Leela. “The IVF paradigm is retrieving oocytes and making embryos. It’s really devastating when that doesn’t work.”

It can be especially devastating and unexpected for younger women with no known risks for infertility and who, according to their age, should still be well within the window of optimal egg quality. “While that curve [of the relationship between maternal age and egg abnormalities] does represent on average the whole population, there are outliers,” says Leela. “There are some people who are young who have a whole lot of abnormal eggs. And there are some people who have advanced maternal age who have totally chromosomally normal eggs, which is not what you’d expect.”

Leela was interested in delving deeper into this pool of outliers. “There has to be something other than the typical age-related mechanisms at play for those individuals,” she said. “We decided to investigate how genetic variations influence egg quality to determine what’s driving this age-disproportionate change in quality.”

Leela conducted her research in the lab of Dr. Schindler, who has been interested in this very question for nearly a decade. “Probably a year after I started [at Rutgers], [my colleague]…showed me the data on how with increasing maternal age, you get a signature curve of aneuploidy, but there were patients who were all over the place,” says Dr. Schindler. Over the next several years, she and her colleagues began investigating whether a genetic link could explain age-unrelated aneuploidy.

“When Leela came online, we knew that we had this family of proteins called kinesins,” explains Dr. Schindler. “Leela was helpful in screening them, and she was captured by the interesting phenotypes of this particular kinesin called KIF18A. That’s how her project started.”

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

The Project

Leela worked within Dr. Schindler’s lab to review bio samples from nearly 3,000 patients who demonstrated high rates of aneuploidy relative to their age, then identified genetic variants within this population using genetic sequencing.

She created a mouse model to study whether certain genetic variants, including KIF18A, could be causally associated with poor egg quality.

“With a mouse model, we move into a biological system and test [the variant] in cells,” she explains. “We ask: if we keep all the other genes exactly the same and just change this variant, can we make eggs that are chromosomally abnormal?”

Leela conducted this experiment with a number of variants and screened several mutations she had identified in high-aneuploidy people.

Ultimately, she found that KIF18A was sufficient to increase the rate of genetic abnormality in the mouse eggs -- which suggests similar rates of aneuploidy in human eggs.

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

Clip from 2022 AMA Research Challenge Finals

What A Genetic Biomarker For Miscarriages Means For Those TTC

To Leela, identifying KIF18A’s association with aneuploidy is a first step in better understanding an individual’s risk of miscarriage.

“[The mouse model we constructed] helps to establish this variant as causal,” Leela explains. “That needs to be done with many different variants, so we could ultimately develop a panel to understand an individual’s fertility profile.”

The hope, according to Leela, would be to help individuals understand their genetic assessment well before they begin trying to conceive.

While Leela studied the particular phenotype of increased aneuploidy relative to age, she notes that multiple genetic variants exist that are known to affect egg quality. She references one case of a genetic encoding beta tubulin that causes oocyte maturation arrest: a condition in which oocytes do not mature and cannot be fertilized.

“There are something like 50 different variants listed in the databases that are associated with pathogenicity in that particular phenotype,” she says. “And yet, that’s not a genetic test that’s routinely ordered. Some of that is clinical reasoning -- most people don’t have any of those genetic variants. But if you are that person who does, it would be nice to know. It’s nice to be empowered and to be aware of what’s going on inside your body.”

In Leela’s ideal future state, women could be empowered with this information by way of a simple blood test, which they could undergo months or even years before they begin trying to conceive.

“In this era of genomic medicine and the DNA sequencing revolution, we deserve to have insight into how our bodies work and what’s going on,” says Leela. “The technology is there. That, I think, is a point of urgency for women everywhere. It’s career-changing. It’s life-changing.”

To Dr. Schindler, who has devoted her career to studying these questions, it’s foundational. “If I were [a fertility] patient, I would want to know why we understand so little about something that is absolutely essential to our lives on this planet,” Dr. Schindler says. “I think about the billions of dollars that go into cancer research. We wouldn’t have cancer if we didn’t exist. Reproductive science is really fundamental to everything else, and yet it is extremely underfunded.”

As she moves to the clinical phase of her MD/PhD program, Leela is undecided about what specialty she will pursue, but one thing is certain: she is bullish on precision medicine, particularly as it relates to reproductive endocrinology and infertility (REI).

“One of the amazing things about fertility and REI as a field is that everyone is always seeking to improve,” she says. “People are doing amazing things, and bringing precision medicine and better genetic testing to empower people before they’re starting to try to conceive is the future.”

See Leela find out that she'd won the 2022 AMA Research Challenge!

Molly Donovan is a writer and content strategist who helps brands and executives develop actionable communications and content strategies and create compelling, authoritative content.

While she loves words, the best thing in her life is her daughter, for whom she and her husband are endlessly grateful to the incredible team at the Brigham and Women’s Center for Infertility and Reproductive Surgery.

You can learn more about her at mdonovancontent.com.